Over recent years, there have been many rapid developments in the field of robotics and artificial intelligence (AI). Not least within health and social care, where technology is changing the face of many settings across the globe.

The scope of robots within the field of medicine means they are poised to become one of the most important innovations of this century and have the potential to fill identified gaps in current health provision.

In response to this, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care Jeremy Hunt recently announced the launch of an independent nationwide review into the use of AI and robotics within the NHS.

The review will look at bionanotechnology and robotics, genomics, machine learning and artificial intelligence, digitalisation and data analytics. The potential application of these developing technologies will be investigated and the review will consider how these opportunities can be maximised to improve NHS services and ensure a sustainable future.

AI and robotics are already present in a wealth of health contexts, carrying out tasks ranging from delivering behavioural training for people with learning disabilities, facilitating rehabilitation exercises, providing reminders to eat or take medication, and even assisting with surgeries.

Providing social interaction to combat isolation and loneliness in patients suffering from chronic illness or in an immunocompromised state is another example of the beneficial usage of robotics.

The tailored communication tools that have been designed by No Isolation, a Norwegian company which has cited ending loneliness as its primary goal, have already begun altering lives in the UK and worldwide. Their robots tackle social isolation, which has been proven to have a serious impact on physical and mental health.

Their primary invention is the AV1 robot, which is designed to act as the eyes, ears and general avatar of the more than 70,000 children in the UK who miss out on school and other childhood activities due to illness, providing them with a conduit to the outside world.

Robotic animals are also starting to make waves as a means to reduce stress and isolation, promote social interaction, facilitate emotional expression, and improve mood and speech fluency in elderly people and those living with dementia.

Care South, which operates 17 residential care homes across the south of England, has introduced animatronic robot “pets” into two of its care homes so far and has noticed an overwhelmingly positive impact.

For residents, the introduction of these innovative pets has provided stimulation, comfort and companionship which has in turn helped to encourage interaction, calm anxieties and improve general relations between residents and caregivers.

RCN member and Clinical Lead for Care South Sarah Small, says: “The robotic animals have been received by our residents incredibly positively. Even though they recognise that they aren’t real, residents still seem to enjoy all the same benefits as they would from having a real pet. We’ve noticed quieter residents become much more engaged and more anxious residents become calmer.”

The robotic pets – two dogs and a pony – are lifelike and interactive with sensor points across their bodies allowing them to respond to being stroked with movement and pleasant noises. Animal therapies are already well established and Care South regularly organises visits from live animals also, which have always been highly successful. The addition of the robotic pets means that residents can now enjoy the same benefits but at any time and for longer periods.

Care South is still using the robotic pets very consciously, aware of the potential risks and ethical complications.

“As with any kind of therapeutic work, it is of course still necessary to be mindful and ensure that what we deliver is appropriate,” Sarah states. “For example, you wouldn’t want to introduce a dog – real or robotic – to someone living with dementia who has had negative experiences of them.”

Sarah is also very clear that they are aware of the potential concerns that use of robotics may ultimately be seen as a way to replace human care givers, ultimately bypassing the vital skills – such as compassion, empathy and human interaction – that are at the heart of the caring professions.

“We would never see this as an either/or situation,” Sarah says. “The robotic animals are not a therapy as such themselves but rather an additional comfort to residents and complimentary to the other therapies and human interaction that remain at the centre of our care.”

After the successful initial trial, more robot pets are being introduced to other Care South homes.

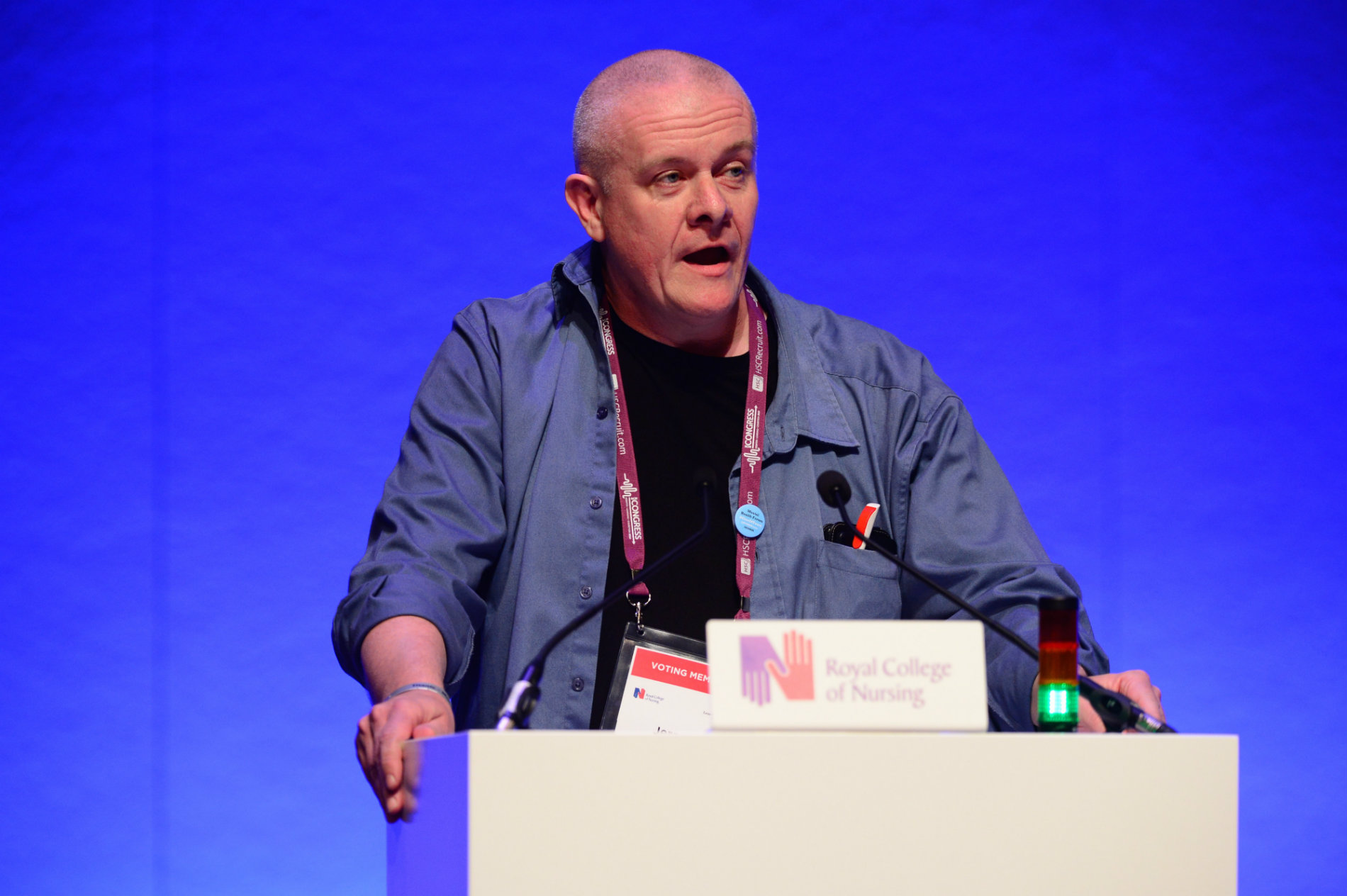

It is both the exciting possibilities and the ethical and safety considerations that led RCN member Gwen Vardigans to propose this as a matter for discussion at this year’s RCN Congress.

“I started to read a lot about robots and AI being used in health care settings and the more I read, the more I realised how beneficial these advancements can be,” Gwen says. “However, it also made me think about the possible shortcomings and ethical considerations that will undoubtedly become more apparent as usage increases.”

During the debate, speakers shared similar conflicted views.

Anthony McGeown described two instances in his workplace where robotics are already being used: for waste collection and disposal, which frees up man hours for more patient-centric care, and the high-tech DaVinci robot that assists in prostatectomy surgery. Despite these useful advancements, he still emphasised that these were "robotic assistance and shouldn’t replace any health care professions."

Phil Noyes also stated that it is essential to "define, refine and protect the unique selling point of human contact" while still being able to benefit from changing technologies.

Several people were also concerned about the possibility for robot hardware to be hacked, which could result in sensitive data being held to ransom or, even worse, patients being harmed during procedures.

Jess Moorhouse cited the NHS hack last year which affected 80 trusts and resulted in five A&E departments being unable to treat patients.

Jennifer Charlewood also talked about this and stressed: “We need to prepare and look into how we are going to shift as a profession to keep up with these changes.”

Gwen returned to the podium to bring the discussion to a close, returning to the reality of the increasing number of people who are suffering loneliness and related health problems that could be eased through possible robotic developments.